|

| The Ol' Perfessor |

For this last chapter of the Big Band leaders of the late 1930s-early 1940s, the topic turns to the happiest and, all things considered (Exhibit A and Exhibit B) the least sociopathic.

“This band was secure enough to be downright silly, something the Millers and Goodmans would never have done.”

I’m not sure why they dragged Glenn Miller into this. He seemed like one of the nice ones. Also, this:

“He was one of the most outrageous, over the top performers of the whole swing era. From the late 30s to the late 40s he was the physical embodiment of the word success, with eleven #1 records and thirty-five top tens! He starred in seven feature films with such co-stars as Lucille Ball, John Barrymore, Karloff, Lugosi, Lorre. Kyser kept his radio show, Kay Kyser's Kollege of Musical Knowledge in the top ten for eleven years on NBC, yet if you ask the average swing fan about him today, they'll likely reply, ‘Kay Kyser. Who's she?’”

James Kern Kyser, who later found fame as Kay Kyser, was born in Rocky Mount, North Carolina to a solid middle-class, two-income family; his mother, Emily Royster (nee Howell) was the first female licensed pharmacist in the state of North Carolina. Unlike the titans of the swing era, Kyser had neither a favored instrument nor a deep passion for music. He did learn the clarinet and played well enough to record a couple sides early in his career, but the role of master entertainer was his true calling. And he would lean into that eventually.

Kyser met North Carolina’s most famous bandleader, Hal Kemp (profiled here) while still in college and Kemp would give him two major lifts to his career. Recognizing his charisma and indefatigable energy, Kemp handed the reins of the University of North Carolina’s band, the Carolina Club Orchestra, to Kyser when he departed to start his own professional band in 1927. Kyser walked in his mentor’s footsteps after graduation, forming a band of his own (ft. saxophonist Sully Mason and with George Duning handling the arranging) and, by touring night spots across the American Midwest, he built up his own following.

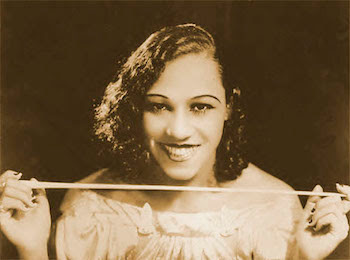

Kemp handed Kyser his second break – and this was the big one – when he recommended Kyser’s band to take over his spot at Chicago’s famous Blackhawk Restaurant in 1934. Having a stable job helped him land talent – he had Merwyn Bogue, aka, “Ish Kabibble” (a spin on “Ish Ga Bibble” which loosely translates to “I should worry”) since 1931, but he added future stars Ginny Simms and “Handsome” Harry Babbit during his time at the Blackhawk – and the band started to record Duning’s arrangements, the most famous being the song that would become his theme, “Thinking of You.” But it took a brainstorm Kyser, et, al. to make him a household name during the war years.

“This band was secure enough to be downright silly, something the Millers and Goodmans would never have done.”

I’m not sure why they dragged Glenn Miller into this. He seemed like one of the nice ones. Also, this:

“He was one of the most outrageous, over the top performers of the whole swing era. From the late 30s to the late 40s he was the physical embodiment of the word success, with eleven #1 records and thirty-five top tens! He starred in seven feature films with such co-stars as Lucille Ball, John Barrymore, Karloff, Lugosi, Lorre. Kyser kept his radio show, Kay Kyser's Kollege of Musical Knowledge in the top ten for eleven years on NBC, yet if you ask the average swing fan about him today, they'll likely reply, ‘Kay Kyser. Who's she?’”

James Kern Kyser, who later found fame as Kay Kyser, was born in Rocky Mount, North Carolina to a solid middle-class, two-income family; his mother, Emily Royster (nee Howell) was the first female licensed pharmacist in the state of North Carolina. Unlike the titans of the swing era, Kyser had neither a favored instrument nor a deep passion for music. He did learn the clarinet and played well enough to record a couple sides early in his career, but the role of master entertainer was his true calling. And he would lean into that eventually.

Kyser met North Carolina’s most famous bandleader, Hal Kemp (profiled here) while still in college and Kemp would give him two major lifts to his career. Recognizing his charisma and indefatigable energy, Kemp handed the reins of the University of North Carolina’s band, the Carolina Club Orchestra, to Kyser when he departed to start his own professional band in 1927. Kyser walked in his mentor’s footsteps after graduation, forming a band of his own (ft. saxophonist Sully Mason and with George Duning handling the arranging) and, by touring night spots across the American Midwest, he built up his own following.

Kemp handed Kyser his second break – and this was the big one – when he recommended Kyser’s band to take over his spot at Chicago’s famous Blackhawk Restaurant in 1934. Having a stable job helped him land talent – he had Merwyn Bogue, aka, “Ish Kabibble” (a spin on “Ish Ga Bibble” which loosely translates to “I should worry”) since 1931, but he added future stars Ginny Simms and “Handsome” Harry Babbit during his time at the Blackhawk – and the band started to record Duning’s arrangements, the most famous being the song that would become his theme, “Thinking of You.” But it took a brainstorm Kyser, et, al. to make him a household name during the war years.