|

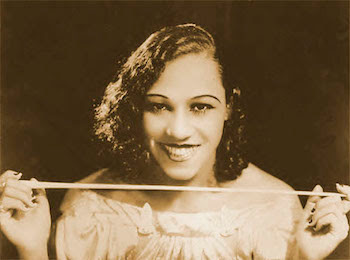

| Damn legend. |

As noted in the prior chapter on Cab Calloway, he grew up in the shadow of his older sister, Blanche Calloway. Pulling from multiple sources, first quoted from a website called Jazz Rhythm:

“Cab Calloway borrowed key elements from his elder sister’s act -- her bravura vocal style and Hi-de-Ho call and response routines. His 1976 memoir acknowledges her influence, declaring Blanche ‘vivacious, lovely, personality plus and a hell of a singer and dancer,’ an all-around entertainer who was ‘fabulous, happy and extroverted.’”

Now, from a site called The LeEMS Machine:

“She is relentlessly written about as residing in the shadow of her younger brother Cab Calloway. However, scholars and researchers have pointed out that, at one point, Blanche Calloway had attained more fame and renown, helping her brother in his show business breakthrough and inspiring his famous style.”

She would wind up living in Cab's shadow by the end of the 1930s, but, all things considered, Blanche Calloway arguably had the bigger life; it wouldn’t surprise me if neither one of them cared one way or the other. He borrowed from her style, she borrowed phrasing and characters from his songs (see cameos by Minnie the Moocher and the King of Sweden in Blanche Calloway’s hit, “Growlin’ Dan”), and so on. Both Calloways made their mark during the period when white audiences finally woke up to what black artists had been doing for decades. In this chapter, the “Hi De Ho Man” makes room for the woman who started her famous “Just a Crazy Song” with “Hi Hi Hi.”

Like her younger brother, Blanche Calloway was born in Rochester, New York, only five years earlier, in 1902. The family returned to their real home, Baltimore, Maryland, when Blanche was a teenager, with their mother, Martha Eulalia Reed, and her second husband, an insurance salesman named John Nelson Fortune.A church organist, Ms. Reed taught her children to play and love music, while trying to steer them away from careers in music, and she failed with at least three of them. In Blanche’s case, the betrayal came at the hands of a music teacher who pushed her to audition with a local talent scout. After Blanche dropped out of Morgan State College in the early 1920s, she wouldn’t hold another straight job until somewhere around the end of World War II.

After working her way to bigger roles in a traveling cabaret outfit called the Smarter Set Co., Calloway landed her first paying job in 1921 with the Baltimore production of the ground-breaking musical revue, Eubie Blake’s and Noble Sissle’s Shuffle Along (which richly deserves a chapter of its own, but I didn’t build this series around Broadway; at any rate, they should make a movie out of that damned-inspiring story). Per Wikipedia, her next gig, a role in the touring production of Plantation Days, which gave her a chance to perform with one of her idols, Florence Mills, and put her in front of audiences across the country. When the tour ended in Chicago, aka, the Jazz Capital of the Country, she decided to stay (and this is where Cab caught up with her, where she opened doors for him, etc.).

Before digging into the rest, a caveat: Wikipedia’s timeline is a goddamn mess. [Ed. - The rest are much better, but, onward...] Her time with Plantation Days ended in 1927, but that source alternately talks about her building a reputation in Chicago, but also moving to New York to play the Ciro Club in the mid-1920s, then moving to Chicago after her time at the Ciro Club. All that’s probably best summed up by “she toured nationally,” but, at some point in the mid-to-late 1920s, she made Chicago's Sunset Café - aka, the same venue that would later launch Louis Armstrong’s career - her main stage. Related, she made her first recordings in 1925 with her first “Joy Boys Orchestra” in 1925 with Armstrong as a member (probably on cornet at that time).

Andy Kirk and his Clouds of Joy orchestra became her next step up the ladder, a period that arguably saw the beginning of Blanche Calloway’s prime. Her time with Kirk saw her write her signature song, “I Need Lovin’” (a frisky number, fwiw), as well as a flash of the confidence that would carry her through the rest of her career. A pair of sources note Calloway’s attempt to take over bandleader’s duties from Kirk, an attempt he thwarted (for a time), but they give slightly different takes on what she gained from the experience. However it happened, a blog called Vintage Innprovides the tightest narrative:

“While touring with the orchestra she quickly found herself the featured attraction. Watching her popularity soar she made an attempt to steal leadership of the group from Kirk. When Kirk figured out the plot he quickly dumped her.”

Different sources have different ways of describing how it all played out. Wikipedia (which gives at least two takes) goes with a tepid “she learned extensively about music management,” while her African America Registry bio characterizes the time as “giving her momentum.” Again, the timeline gets cloudier than muddy - e.g., Wikipedia pegs her time with/attempted takeover of Kirk’s band in 1931, while also stating she recorded with the first orchestra she led in the same year. At any rate the final and most famous iteration of Her Joy Boys - the line-up that played New York City’s most famed venues (e.g., the Lafayette Theatre, the Harlem Opera House, and the Apollo Theatre) - featured a line-up that included Cozy Cole and Chick Webb (two friends from Calloway’s Baltimore days), plus Bennie Moten, Zack Wythe and…Andy Kirk, who, sure, might have joined up in the early/mid 1930s, but I find it hard to believe it was a different Andy Kirk. So…she did take over in the end? Then there’s the forgotten Edgar “Puddin Head” Battle, who Vintage Inn credits with helping Calloway form Her Joy Boys after Kirk chucked her.

However it came together, and whoever she played with, Blanche Calloway had her best years in the first half of the 1930s. She recorded some of her biggest songs during this period - e.g., “Just a Crazy Song,” “Make Me Know It,” “You Ain’t Livin’ Right,” plus two more Calloway wrote, “Rhythm River,” and “Growlin’ Dan.”

Things slowed down for Calloway after 1935, something Wikipedia speculates might have followed from her younger brother’s growing fame (but who trusts them at this point?), but all sources flag one disastrous incident that might have proved decisive. While touring the Deep South in 1936, Calloway and a member of her orchestra got arrested and spent a night in the Yazoo, Mississippi jail after some “concerned citizen” (read: a massive asshole) called the cops after seeing Calloway and the wife of someone in her orchestra use a “ladies room” at a Shell gas station. Once again, the sources disagree on major details [Ed. - sources can’t even agree on the identity of Blanche Calloway’s husbands], but LeEMS Machine gives the fullest account: having grown up outside the Deep South, neither woman understood “ladies room” to mean white women only, but had crossed the street to a café by the time the cops rolled up; the first person they found when they arrived was Norman Pinder, Calloway’s husband (maybe?!), so they accosted him; when he failed to understand the question/bullshit, they pistol-whipped “repeatedly” for having the gall and jailed both Calloway and Pinder (or someone else…who knows?) overnight for “disorderly conduct” on top of a fine of $7.50. And, to cap off what surely rated among the shittiest nights of Balance Calloway’s life, another band-member ran off with the band’s money and stranded all concerned in backwater Yazoo.

The whole ordeal ended with Calloway selling her yellow Cadillac to get home and, possibly, the 1938 bankruptcy that ended her best days…in show business anyway. The incident made national news and also included the tiniest glimmers of social progress. From LeEMS Machine:

“The deplorable incident made national news and resulted in letters of protest from the NAACP, letters of apology from Shell petroleum company headquarters in New York, and a boycott of Shell gas stations by African Americans.”

While Calloway made a couple more runs at a career in show business - e.g., forming an all-female orchestra in the 1940s and running a Washington D.C. night club called Crystal Caverns in the 1950s (where she platformed a singer named Ruth Brown) - the bulk of her second act came in the unlikely field of politics. When she moved to Florida in the late 1950s to work as a DJ with Miami’s WMBM, she got involved at the local level. In 1958, she became the first black precinct voting clerk in Florida and, in the same year, the first black woman to vote in the state of Florida. By the early 1960s, she became an active member of the NAACP - including ground-level work like sitting-in at the lunch counter at Grant’s Store to confirm they’d desegregated - on top of joining the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and serving on the board of the Urban League.

And, yet, I found something else she did more revolutionary than all that. From LeEMS Machine, one more time:

“In 1968 she formed Afram House, a mail order cosmetics company, in order to provide African American women with cosmetics, wigs, and accessories designed for a darker skin tone. The company was expanding into real-estate by 1970s, with plans to open a chain of stores.”

That's just Blanche Calloway having a conversation that major cosmetic compaines (and America as a whole), still hasn’t entirely worked out 50 years later. I’ve read scores of interviews, bios and histories of musical artists by now - hell, I’m probably into the low hundreds by now - and few have impressed me as much as Blanche Calloway’s. To be that far ahead of your time on something at once obvious and nuanced...helluva a woman.

About the Sampler

Spotify only had a pair of collections by Blanche Calloway, and I’m going to post the bigger of the two on twitter when this post goes up. Whatever I think of her as a trailblazer/hero, her music sounds less, for lack of a better hyphenated phrase, forward-modern than Cab Calloway’s. To my barely-trained ear, it sounds closer to the 1920s New Orleans jazz style than the big band sound of the 1930s - which could have something to do with the fact that her career petered out before Benny Goodman (somehow) managed to kick off the Big Band Era. At any rate, to expand on the sampling above with some tunes from the Blanche Calloway (Doxy Collection), enjoy: “Lazy Woman’s Blues,” “Loveless Love,” “Misery,” “Louisiana Liza,” “Last Dollar,” “Without That Gal!” (fairly big band, fwiw), “It Looks Like Suzie,” "I Gotta Swing," “I Got What It Takes” (sounds most like Cab's phrasing, for my money), and “What’s a Poor Girl Gonna Do.” And I’m still glad I took the time…till the next one…

“Cab Calloway borrowed key elements from his elder sister’s act -- her bravura vocal style and Hi-de-Ho call and response routines. His 1976 memoir acknowledges her influence, declaring Blanche ‘vivacious, lovely, personality plus and a hell of a singer and dancer,’ an all-around entertainer who was ‘fabulous, happy and extroverted.’”

Now, from a site called The LeEMS Machine:

“She is relentlessly written about as residing in the shadow of her younger brother Cab Calloway. However, scholars and researchers have pointed out that, at one point, Blanche Calloway had attained more fame and renown, helping her brother in his show business breakthrough and inspiring his famous style.”

She would wind up living in Cab's shadow by the end of the 1930s, but, all things considered, Blanche Calloway arguably had the bigger life; it wouldn’t surprise me if neither one of them cared one way or the other. He borrowed from her style, she borrowed phrasing and characters from his songs (see cameos by Minnie the Moocher and the King of Sweden in Blanche Calloway’s hit, “Growlin’ Dan”), and so on. Both Calloways made their mark during the period when white audiences finally woke up to what black artists had been doing for decades. In this chapter, the “Hi De Ho Man” makes room for the woman who started her famous “Just a Crazy Song” with “Hi Hi Hi.”

Like her younger brother, Blanche Calloway was born in Rochester, New York, only five years earlier, in 1902. The family returned to their real home, Baltimore, Maryland, when Blanche was a teenager, with their mother, Martha Eulalia Reed, and her second husband, an insurance salesman named John Nelson Fortune.A church organist, Ms. Reed taught her children to play and love music, while trying to steer them away from careers in music, and she failed with at least three of them. In Blanche’s case, the betrayal came at the hands of a music teacher who pushed her to audition with a local talent scout. After Blanche dropped out of Morgan State College in the early 1920s, she wouldn’t hold another straight job until somewhere around the end of World War II.

After working her way to bigger roles in a traveling cabaret outfit called the Smarter Set Co., Calloway landed her first paying job in 1921 with the Baltimore production of the ground-breaking musical revue, Eubie Blake’s and Noble Sissle’s Shuffle Along (which richly deserves a chapter of its own, but I didn’t build this series around Broadway; at any rate, they should make a movie out of that damned-inspiring story). Per Wikipedia, her next gig, a role in the touring production of Plantation Days, which gave her a chance to perform with one of her idols, Florence Mills, and put her in front of audiences across the country. When the tour ended in Chicago, aka, the Jazz Capital of the Country, she decided to stay (and this is where Cab caught up with her, where she opened doors for him, etc.).

Before digging into the rest, a caveat: Wikipedia’s timeline is a goddamn mess. [Ed. - The rest are much better, but, onward...] Her time with Plantation Days ended in 1927, but that source alternately talks about her building a reputation in Chicago, but also moving to New York to play the Ciro Club in the mid-1920s, then moving to Chicago after her time at the Ciro Club. All that’s probably best summed up by “she toured nationally,” but, at some point in the mid-to-late 1920s, she made Chicago's Sunset Café - aka, the same venue that would later launch Louis Armstrong’s career - her main stage. Related, she made her first recordings in 1925 with her first “Joy Boys Orchestra” in 1925 with Armstrong as a member (probably on cornet at that time).

Andy Kirk and his Clouds of Joy orchestra became her next step up the ladder, a period that arguably saw the beginning of Blanche Calloway’s prime. Her time with Kirk saw her write her signature song, “I Need Lovin’” (a frisky number, fwiw), as well as a flash of the confidence that would carry her through the rest of her career. A pair of sources note Calloway’s attempt to take over bandleader’s duties from Kirk, an attempt he thwarted (for a time), but they give slightly different takes on what she gained from the experience. However it happened, a blog called Vintage Innprovides the tightest narrative:

“While touring with the orchestra she quickly found herself the featured attraction. Watching her popularity soar she made an attempt to steal leadership of the group from Kirk. When Kirk figured out the plot he quickly dumped her.”

Different sources have different ways of describing how it all played out. Wikipedia (which gives at least two takes) goes with a tepid “she learned extensively about music management,” while her African America Registry bio characterizes the time as “giving her momentum.” Again, the timeline gets cloudier than muddy - e.g., Wikipedia pegs her time with/attempted takeover of Kirk’s band in 1931, while also stating she recorded with the first orchestra she led in the same year. At any rate the final and most famous iteration of Her Joy Boys - the line-up that played New York City’s most famed venues (e.g., the Lafayette Theatre, the Harlem Opera House, and the Apollo Theatre) - featured a line-up that included Cozy Cole and Chick Webb (two friends from Calloway’s Baltimore days), plus Bennie Moten, Zack Wythe and…Andy Kirk, who, sure, might have joined up in the early/mid 1930s, but I find it hard to believe it was a different Andy Kirk. So…she did take over in the end? Then there’s the forgotten Edgar “Puddin Head” Battle, who Vintage Inn credits with helping Calloway form Her Joy Boys after Kirk chucked her.

However it came together, and whoever she played with, Blanche Calloway had her best years in the first half of the 1930s. She recorded some of her biggest songs during this period - e.g., “Just a Crazy Song,” “Make Me Know It,” “You Ain’t Livin’ Right,” plus two more Calloway wrote, “Rhythm River,” and “Growlin’ Dan.”

Things slowed down for Calloway after 1935, something Wikipedia speculates might have followed from her younger brother’s growing fame (but who trusts them at this point?), but all sources flag one disastrous incident that might have proved decisive. While touring the Deep South in 1936, Calloway and a member of her orchestra got arrested and spent a night in the Yazoo, Mississippi jail after some “concerned citizen” (read: a massive asshole) called the cops after seeing Calloway and the wife of someone in her orchestra use a “ladies room” at a Shell gas station. Once again, the sources disagree on major details [Ed. - sources can’t even agree on the identity of Blanche Calloway’s husbands], but LeEMS Machine gives the fullest account: having grown up outside the Deep South, neither woman understood “ladies room” to mean white women only, but had crossed the street to a café by the time the cops rolled up; the first person they found when they arrived was Norman Pinder, Calloway’s husband (maybe?!), so they accosted him; when he failed to understand the question/bullshit, they pistol-whipped “repeatedly” for having the gall and jailed both Calloway and Pinder (or someone else…who knows?) overnight for “disorderly conduct” on top of a fine of $7.50. And, to cap off what surely rated among the shittiest nights of Balance Calloway’s life, another band-member ran off with the band’s money and stranded all concerned in backwater Yazoo.

The whole ordeal ended with Calloway selling her yellow Cadillac to get home and, possibly, the 1938 bankruptcy that ended her best days…in show business anyway. The incident made national news and also included the tiniest glimmers of social progress. From LeEMS Machine:

“The deplorable incident made national news and resulted in letters of protest from the NAACP, letters of apology from Shell petroleum company headquarters in New York, and a boycott of Shell gas stations by African Americans.”

While Calloway made a couple more runs at a career in show business - e.g., forming an all-female orchestra in the 1940s and running a Washington D.C. night club called Crystal Caverns in the 1950s (where she platformed a singer named Ruth Brown) - the bulk of her second act came in the unlikely field of politics. When she moved to Florida in the late 1950s to work as a DJ with Miami’s WMBM, she got involved at the local level. In 1958, she became the first black precinct voting clerk in Florida and, in the same year, the first black woman to vote in the state of Florida. By the early 1960s, she became an active member of the NAACP - including ground-level work like sitting-in at the lunch counter at Grant’s Store to confirm they’d desegregated - on top of joining the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and serving on the board of the Urban League.

And, yet, I found something else she did more revolutionary than all that. From LeEMS Machine, one more time:

“In 1968 she formed Afram House, a mail order cosmetics company, in order to provide African American women with cosmetics, wigs, and accessories designed for a darker skin tone. The company was expanding into real-estate by 1970s, with plans to open a chain of stores.”

That's just Blanche Calloway having a conversation that major cosmetic compaines (and America as a whole), still hasn’t entirely worked out 50 years later. I’ve read scores of interviews, bios and histories of musical artists by now - hell, I’m probably into the low hundreds by now - and few have impressed me as much as Blanche Calloway’s. To be that far ahead of your time on something at once obvious and nuanced...helluva a woman.

About the Sampler

Spotify only had a pair of collections by Blanche Calloway, and I’m going to post the bigger of the two on twitter when this post goes up. Whatever I think of her as a trailblazer/hero, her music sounds less, for lack of a better hyphenated phrase, forward-modern than Cab Calloway’s. To my barely-trained ear, it sounds closer to the 1920s New Orleans jazz style than the big band sound of the 1930s - which could have something to do with the fact that her career petered out before Benny Goodman (somehow) managed to kick off the Big Band Era. At any rate, to expand on the sampling above with some tunes from the Blanche Calloway (Doxy Collection), enjoy: “Lazy Woman’s Blues,” “Loveless Love,” “Misery,” “Louisiana Liza,” “Last Dollar,” “Without That Gal!” (fairly big band, fwiw), “It Looks Like Suzie,” "I Gotta Swing," “I Got What It Takes” (sounds most like Cab's phrasing, for my money), and “What’s a Poor Girl Gonna Do.” And I’m still glad I took the time…till the next one…

No comments:

Post a Comment