|

| Plan A, apparently. |

The Hit

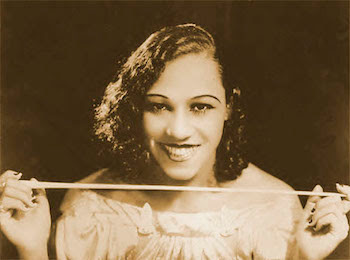

Anita Ward was working as an elementary school teacher when she recorded her sultry, literal chart-topping single, “Ring My Bell” in 1979. After graduating from Rust University, majoring in Psychology, she had no intention of embarking on a music career, but, as Stereogum (helpfully!) noted in a 2020 entry in a series that shares the same theme as this series (Numbers Ones), a school administrator at Rust U. heard her audition for Godspell (I can just hear here on “Turn Back, Oh, Man”), and offered to become her manager. Said administrator put her in touch with Frederick Knight, a local celebrity in his own right, by way of his regional/Stax Records hit “I’ve Been Lonely for So Long.”

Knight had originally written “Ring My Bell” for Stacy Lattislaw, “an 11-year-old kiddie-R&B singer,” but he sexed up the lyrics for Ward, though Ward was, per Stereogum’s article, “a clean-living Christian girl.” [Ed. - Though, here, “sexed up” means loosely implying that sex is something that might happen when someone comes home from work.] It was the last song they recorded for Ward’s debut album, but it shot to No. 1 within two weeks. Ward even switched to substitute teaching just in case the single took off. And it very much did, hitting No. 1 in the U.S., the UK and Canada.

Another fun (probably) fact: “Ring My Bell” was the No. 1 single in America on the night of Chicago’s rightly infamous Disco Demolition Night, a detail that became the lede/nugget for Stereogum’s piece. To quote/contextualize in full:

“Disco was a form of underground music that had improbably risen up out of New York’s black and gay clubs to conquer the pop charts. It upended social norms, changed fashion and drugs, and moved the balance of music-business power away from the petty-aristocrat California singer-songwriters who’d been running things up until then. From a music-history standpoint, it’s possible to see disco as a great democratizing force, a push to turn pop music into something fun and silly and cheap and glamorous. When people like Chic’s Nile Rodgers describe Disco Demolition Night as a fascist rally, that’s what they’re talking about.”

For fans of podcasts, there’s a really good episode of You’re Wrong About on the same subject, for what it’s worth. Anita Ward does not make a cameo…

As a piece of music, it’s pure dance/disco, content with repetition - does that single-note pulse on the one ever let up? [Ed. - After the first verse, yes, it does…only to return around the third minute] - and even-keeled to a fault. It’s a song to get lost in, a mix of ecstatic and primal; a vehicle for the dance-floor. On the production side, it foregrounds the hooks, so you don’t really hear the rhythm, but, those backing vocals are one of your better hooks. It’s hard to believe something so hypnotic can only happen once for one artist…

Anita Ward was working as an elementary school teacher when she recorded her sultry, literal chart-topping single, “Ring My Bell” in 1979. After graduating from Rust University, majoring in Psychology, she had no intention of embarking on a music career, but, as Stereogum (helpfully!) noted in a 2020 entry in a series that shares the same theme as this series (Numbers Ones), a school administrator at Rust U. heard her audition for Godspell (I can just hear here on “Turn Back, Oh, Man”), and offered to become her manager. Said administrator put her in touch with Frederick Knight, a local celebrity in his own right, by way of his regional/Stax Records hit “I’ve Been Lonely for So Long.”

Knight had originally written “Ring My Bell” for Stacy Lattislaw, “an 11-year-old kiddie-R&B singer,” but he sexed up the lyrics for Ward, though Ward was, per Stereogum’s article, “a clean-living Christian girl.” [Ed. - Though, here, “sexed up” means loosely implying that sex is something that might happen when someone comes home from work.] It was the last song they recorded for Ward’s debut album, but it shot to No. 1 within two weeks. Ward even switched to substitute teaching just in case the single took off. And it very much did, hitting No. 1 in the U.S., the UK and Canada.

Another fun (probably) fact: “Ring My Bell” was the No. 1 single in America on the night of Chicago’s rightly infamous Disco Demolition Night, a detail that became the lede/nugget for Stereogum’s piece. To quote/contextualize in full:

“Disco was a form of underground music that had improbably risen up out of New York’s black and gay clubs to conquer the pop charts. It upended social norms, changed fashion and drugs, and moved the balance of music-business power away from the petty-aristocrat California singer-songwriters who’d been running things up until then. From a music-history standpoint, it’s possible to see disco as a great democratizing force, a push to turn pop music into something fun and silly and cheap and glamorous. When people like Chic’s Nile Rodgers describe Disco Demolition Night as a fascist rally, that’s what they’re talking about.”

For fans of podcasts, there’s a really good episode of You’re Wrong About on the same subject, for what it’s worth. Anita Ward does not make a cameo…

As a piece of music, it’s pure dance/disco, content with repetition - does that single-note pulse on the one ever let up? [Ed. - After the first verse, yes, it does…only to return around the third minute] - and even-keeled to a fault. It’s a song to get lost in, a mix of ecstatic and primal; a vehicle for the dance-floor. On the production side, it foregrounds the hooks, so you don’t really hear the rhythm, but, those backing vocals are one of your better hooks. It’s hard to believe something so hypnotic can only happen once for one artist…