|

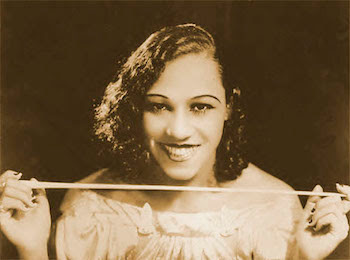

| Classic line-up. |

Overall, the Mills Brothers’ story is one of a steady climb to success, if with a side of tragedy. Even the tragedy followed from their success, if accidentally.

The four Mills Brothers - from oldest to youngest, John Jr., Herbert, Harry and Donald - were born between 1910 and 1915 and into a family that ultimately included nine children. Their parents raised them in Piqua, Ohio, a town north of Dayton, in what sounds like a comfortable and musical environment. Their mother, Ethel, sang light opera and their father, John Mills, Sr., both ran a barbershop and sang in a barbershop quartet called The Four Kings of Harmony. John Sr. taught his boys everything he knew, but he had no way of knowing how far they’d take it. And, in the end, him.

They learned music singing in a pair of church choirs growing up (Cyrene African Methodist Episcopal and Park Avenue Baptist) and put that knowledge into practice at impromptu performances in front of their father’s barbershop with a kazoo for accompaniment. They officially formed the act in 1925 and started working around Southwest Ohio playing house/lawn parties, at music halls and supper clubs. If their official career started anywhere, it would be Piqua’s May’s Opera House where they found work singing between Rin-Tin-Tin features. When the same venue hosted an amateur contest, the Mills Brothers signed on - and stumbled into what became their, for lack of a better word, gimmick:

“They entered an amateur contest at May's Opera House but while on stage Harry realized he had lost his kazoo. He improvised by cupping his hand over his mouth and mimicking the sound of trumpet. The brothers liked the idea and worked it into their act. John, the bass vocalist, would imitate the tuba. Harry, a baritone, imitated the trumpet, Herbert became the second trumpet, and Donald the trombone. John accompanied the four-part harmony on ukulele and then guitar. They practiced imitating orchestras they heard on the radio.”

The Rin-Tin-Tin gig opened its first door in 1928, when the Mills Brothers traveled to Cincinnati with the Harold Greenameyer’s orchestra for an audition at WLW Radio; the station manager passed on Greenameyer & Co., but hired the Mills Brothers. Though they quickly established a solid local following and brought the entire Mills family to a new city, the Mills Brothers didn't wait long for their next big break. When Duke Ellington and His Orchestra passed through Cincinnati, someone arranged to have them sing for him. Impressed by what he heard, Ellington referred them to his New York contact at Okeh Records, Tommy Rockwell, who quickly signed them. That took them to New York and one small step from the national stage.

The four Mills Brothers - from oldest to youngest, John Jr., Herbert, Harry and Donald - were born between 1910 and 1915 and into a family that ultimately included nine children. Their parents raised them in Piqua, Ohio, a town north of Dayton, in what sounds like a comfortable and musical environment. Their mother, Ethel, sang light opera and their father, John Mills, Sr., both ran a barbershop and sang in a barbershop quartet called The Four Kings of Harmony. John Sr. taught his boys everything he knew, but he had no way of knowing how far they’d take it. And, in the end, him.

They learned music singing in a pair of church choirs growing up (Cyrene African Methodist Episcopal and Park Avenue Baptist) and put that knowledge into practice at impromptu performances in front of their father’s barbershop with a kazoo for accompaniment. They officially formed the act in 1925 and started working around Southwest Ohio playing house/lawn parties, at music halls and supper clubs. If their official career started anywhere, it would be Piqua’s May’s Opera House where they found work singing between Rin-Tin-Tin features. When the same venue hosted an amateur contest, the Mills Brothers signed on - and stumbled into what became their, for lack of a better word, gimmick:

“They entered an amateur contest at May's Opera House but while on stage Harry realized he had lost his kazoo. He improvised by cupping his hand over his mouth and mimicking the sound of trumpet. The brothers liked the idea and worked it into their act. John, the bass vocalist, would imitate the tuba. Harry, a baritone, imitated the trumpet, Herbert became the second trumpet, and Donald the trombone. John accompanied the four-part harmony on ukulele and then guitar. They practiced imitating orchestras they heard on the radio.”

The Rin-Tin-Tin gig opened its first door in 1928, when the Mills Brothers traveled to Cincinnati with the Harold Greenameyer’s orchestra for an audition at WLW Radio; the station manager passed on Greenameyer & Co., but hired the Mills Brothers. Though they quickly established a solid local following and brought the entire Mills family to a new city, the Mills Brothers didn't wait long for their next big break. When Duke Ellington and His Orchestra passed through Cincinnati, someone arranged to have them sing for him. Impressed by what he heard, Ellington referred them to his New York contact at Okeh Records, Tommy Rockwell, who quickly signed them. That took them to New York and one small step from the national stage.