|

| A glimpse ahead...and mind the names. |

With boogie-woogie, we finally have a genre with a fairly specific origin story. Most sources name north Texas as the birthplace, with Marshall, Texas as the specific locale and the lumber/turpentine camps on the Texas/Louisiana border as petri-dish of its evolution. With those camps situated near the lumber - aka, the middle of nowhere - the men they employed left their homes to work in the camps. As noted in a short 1986 history on an old UK program called South Bank Show, they spent long days alternating between working lumber and turpentine. They needed to unwind after they knocked off work, so juke joints and barrel houses popped up near the camps to serve the familiar entertainment of dancing and drinking. It moved on from those hard-scabble beginnings in no time: some of the blues greats like Blind Lemon Jefferson, Jelly Roll Morton and Lead Belly, recall hearing it in the various joints and venues they played.

A second factor, and one often cited as an inspiration for the sound, was the introduction of the railroad to northeast Texas shortly after the Civil War. Marshall was the hub for a semi-independent railroad system (you keep doing you, Texas) that came up by way of New Orleans and reached out into the lumber region known as Piney Woods. As the rails grew to service not just the lumber industry, but also oil and cattle industry, traveling boogie-woogie musicians would hop trains from one camp to the next, spreading the boogie-woogie style as they went. As the rails expanded, they carried it to east Texas’ major cities - e.g., Dallas, Houston and Galveston, places where it was also known as “fast western” - and from there to New Orleans (where, incidentally, a different sub-genre took root) and later to north to Chicago.

The theory goes that the anchor of the boogie-woogie sound - a left-hand bass figure, per Wikipedia’s entry, “’eight to the bar’…much of it written in common time (4/4) using eighth notes” and an original standard chord progression of I-IV-V-I (later with “many formal variations”) - got its inspiration from the steady rocking of the trains moving through that country. Many of those “formal variations have names - e.g., “the Marshall,” a simple form named for the city, “the Jefferson," also four-beats-to-the-bar, but goes down a pitch on the last note in each four note cycle,” or other like “the Rocks” or “the Five.” Whatever the variation, that grounded, rhythmic and repetitive bass-line made boogie-woogie ideal for popular (as opposed to formalized) dancing; boogie-woogie is the blues when it wants to get up and dance, basically. As it moved into the cities, the genre became popular for house-rent parties - i.e., parties where guests paid a small fee to get in and the musician(s) and hosts split the door money - spreading its popularity further still.

Boogie-woogie grew up alongside the recording industry, but it also predates it. The earliest time either the word “boogie” or “woogie” appeared came in 1901 with the publishing of “Hoogie Boogie.” No one really knows where the particular pairing of words came, but some candidates include borrowing from various African dialects - e.g., “boog” from Hausa, “booga” from Mandingo (where it means beat or beat a drum), or “Mbuki Mvuki” (definition of the second word is awesome: “to dance wildly, as if to shake off one’s clothes”). Other theories point to blues lore: a site called Rag Piano makes reference to the devil or “bogeyman,” which hints at something to be heard away from polite society. Regardless of where the words originated, one word or the other - “boogie” mostly - started showing up on recordings like 1913’s “That Syncopated Boogie Boo” by “Edison of the ‘American Quartet’” and Wilbur Sweatman’s “Boogie Rag.” [Ed. - disastrous sound on that last one.] And, yes, both of those titles hint at boogie-woogie’s connection to ragtime.

Some of the earlier numbers included neither word in the title. For instance, George W. Thomas, one of boogie-woogie’s great, original proselytizers, first took the sound from the lumber camps to New Orleans with 1910’s “New Orleans Hop Scop Blues.” [Ed. - You'll hear something closer to boogie-woogie in that one.] A guy named Artie Matthews released the first song with “the correct bassline” in 1915, but the title, “Weary Blues,” again left the genre’s name out of it; the same thing happened when the Louisiana Five re-released the song in 1919. George Thomas and his brother, Hirsel, gave a nod to one of the famous boogie-woogie variations noted above on a 1922 release titled “The Five” - a song later re-recorded by Joseph Samuel’s Tampa Blue Jazz Band in 1923 with a New Orleans jazz overlay - but both words wouldn’t appear in a song’s title until Pinetop Smith recorded and released “Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie” in 1928, the genre’s first, clear commercial hit. So let’s talk about Pinetop (or “Pine Top”) Smith.

Born Clarence Smith in Troy, Alabama in 1904, he was the ninth of as many children. Rag Piano provides the fullest telling of his early life, most notably his father’s early death and his older brother Clem stepping up to support the family’s now-widowed mother. He picked up his nickname from a love of climbing tall trees, but it also gives a smart nod to the Piney Woods area, even if I totally made that up. Between his birth and his father’s death, Smith’s family had moved to Birmingham, Alabama, which is where his career in music began. A self-taught pianist, he broke in at age 15 playing house rent parties. Just a year later, he left the South for Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the city where his real education began.

Once in Pennsylvania, Pinetop Smith joined the Theater Owners Booking Association (TOBA) vaudeville circuit. He toured with the company handling everything from playing piano to singing to performing in skits. Paired with early-1920s blues legend, Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, as well as a singing husband/wife comedy team called Butterbean & Susie, he improved his piano playing; no less significantly, all that touring put the still-young Smith into juke joints and barrel houses all over the mid-Atlantic region and the American Southeast, places that exposed him to early blues and, of course, boogie-woogie.

While in Pittsburgh, Smith met another boogie-woogie pianist named Charles Edward “Cow Cow” Davenport, who convinced him to move with his wife, Sarah Horton, and their son to Chicago sometime during winter 1927 or spring 1928. Some mystery surrounds the origin and details of the relationship - for instance, Rag Piano relates a contested history in which Davenport introduced Pinetop Smith to the name “boogie-woogie,” a detail that runs headlong into Smith’s claim of coining the name - but, one thing is clear: Davenport had connections to the music industry in Chicago - and he definitely helped Smith in that regard. Apart from knowing Tampa Red - an important gatekeeper for musicians coming to Chicago during the Great Migration - Davenport was a musician/talent scout connected to Vocalion Records. That lead to introductions to J. Mayo Williams, a major player in the “race record” market in 1920s Chicago and the 1928 recording session that produced “Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie,” plus seven more recordings.

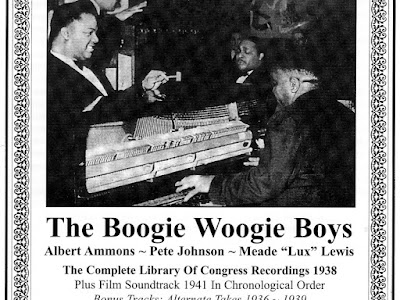

The truth of his claims aside, Davenport arranged a pretty smooth landing in Chicago for Pinetop Smith. He not only helped arrange those sessions, he connected Smith to Albert Ammons and Meade “Lux” Lewis, a couple of pianists who also played boogie-woogie; the three even shared a rooming house together for a time, presumably with Smith’s wife and, now, two children. Smith had another recording session lined up for March 16, 1929, but tragedy struck the budding community literally the day before when a bullet caught him at a dance hall performance. No one knows whether the bullet was intended for Pinetop Smith - it came out of a fight that ended with gunshots - but the headline in Downbeat magazine says it all: “I Saw Pinetop Spit Blood and Fall.” He died at just 25, leaving behind a wife and two kids.

The world kept turning and boogie-woogie continued after Pinetop Smith’s death - e.g., Meade “Lux” Lewis released his first hit, “Honky Tonk Train Blues,” in 1929 - but the Great Depression descended on the nation by the end of that year; when disposable income dried up, so did the record industry. Boogie-Woogie would go into a kind of remission for most of the 1930s. I’ll loop back to the story of its revival and cover the histories of some of the men who revived it - including Ammons and Lewis - in a (much) later post.

About the Sampler

I was happy to find all the songs from Pinetop Smith’s 1928 recording session on Spotify and included all of them on the sampler: in the order they have them, “I Got More Sense Than That,” “Pinetop Blues,” “Now I Ain’t Got Nothing at All,” “Big Boy They Can’t Do That,” “I’m Sober Now,” “Jump Steady Blues,” and, finally, a fantastic spin on a tune made famous by Bessie Smith, “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out.” [Ed. - If there's no link, I couldn't find it.] Beyond the playing - and boogie-woogie’s spirit of fun comes through - Smith gets a lot of personality into his music, enough to make you wistful about what might have been - especially after you hear Ammons’, Lewis’, et al’s later material.

I pushed the sampler to 20 songs by including a couple songs up above - e.g., Meade “Lux” Lewis’ first hit, as well as Albert Ammons’ first, the delightfully busy “Swanee River Boogie” - while also including three to acknowledge George Thomas: “The Rocks” (named for another variation), “Fast Stuff Blues,” and “Don’t Kill Him in Here.” Cow Cow Davenport also gets a nod - five, in fact - with “Chimes Blues,” (personal favorite) “The Mess Is Here,” “State Street Jive” (a duet), “Jim Crow Blues,” and, his most famous number (the one that prompted Pinetop Smith to introduce himself) “Cow Cow Blues.”

I’ve got one last song on there, something I couldn’t help but include as foreshadowing: Big Joe Turner’s “Roll ‘Em Pete.” I’m looking forward to telling that story.

Till the next one…

A second factor, and one often cited as an inspiration for the sound, was the introduction of the railroad to northeast Texas shortly after the Civil War. Marshall was the hub for a semi-independent railroad system (you keep doing you, Texas) that came up by way of New Orleans and reached out into the lumber region known as Piney Woods. As the rails grew to service not just the lumber industry, but also oil and cattle industry, traveling boogie-woogie musicians would hop trains from one camp to the next, spreading the boogie-woogie style as they went. As the rails expanded, they carried it to east Texas’ major cities - e.g., Dallas, Houston and Galveston, places where it was also known as “fast western” - and from there to New Orleans (where, incidentally, a different sub-genre took root) and later to north to Chicago.

The theory goes that the anchor of the boogie-woogie sound - a left-hand bass figure, per Wikipedia’s entry, “’eight to the bar’…much of it written in common time (4/4) using eighth notes” and an original standard chord progression of I-IV-V-I (later with “many formal variations”) - got its inspiration from the steady rocking of the trains moving through that country. Many of those “formal variations have names - e.g., “the Marshall,” a simple form named for the city, “the Jefferson," also four-beats-to-the-bar, but goes down a pitch on the last note in each four note cycle,” or other like “the Rocks” or “the Five.” Whatever the variation, that grounded, rhythmic and repetitive bass-line made boogie-woogie ideal for popular (as opposed to formalized) dancing; boogie-woogie is the blues when it wants to get up and dance, basically. As it moved into the cities, the genre became popular for house-rent parties - i.e., parties where guests paid a small fee to get in and the musician(s) and hosts split the door money - spreading its popularity further still.

Boogie-woogie grew up alongside the recording industry, but it also predates it. The earliest time either the word “boogie” or “woogie” appeared came in 1901 with the publishing of “Hoogie Boogie.” No one really knows where the particular pairing of words came, but some candidates include borrowing from various African dialects - e.g., “boog” from Hausa, “booga” from Mandingo (where it means beat or beat a drum), or “Mbuki Mvuki” (definition of the second word is awesome: “to dance wildly, as if to shake off one’s clothes”). Other theories point to blues lore: a site called Rag Piano makes reference to the devil or “bogeyman,” which hints at something to be heard away from polite society. Regardless of where the words originated, one word or the other - “boogie” mostly - started showing up on recordings like 1913’s “That Syncopated Boogie Boo” by “Edison of the ‘American Quartet’” and Wilbur Sweatman’s “Boogie Rag.” [Ed. - disastrous sound on that last one.] And, yes, both of those titles hint at boogie-woogie’s connection to ragtime.

Some of the earlier numbers included neither word in the title. For instance, George W. Thomas, one of boogie-woogie’s great, original proselytizers, first took the sound from the lumber camps to New Orleans with 1910’s “New Orleans Hop Scop Blues.” [Ed. - You'll hear something closer to boogie-woogie in that one.] A guy named Artie Matthews released the first song with “the correct bassline” in 1915, but the title, “Weary Blues,” again left the genre’s name out of it; the same thing happened when the Louisiana Five re-released the song in 1919. George Thomas and his brother, Hirsel, gave a nod to one of the famous boogie-woogie variations noted above on a 1922 release titled “The Five” - a song later re-recorded by Joseph Samuel’s Tampa Blue Jazz Band in 1923 with a New Orleans jazz overlay - but both words wouldn’t appear in a song’s title until Pinetop Smith recorded and released “Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie” in 1928, the genre’s first, clear commercial hit. So let’s talk about Pinetop (or “Pine Top”) Smith.

Born Clarence Smith in Troy, Alabama in 1904, he was the ninth of as many children. Rag Piano provides the fullest telling of his early life, most notably his father’s early death and his older brother Clem stepping up to support the family’s now-widowed mother. He picked up his nickname from a love of climbing tall trees, but it also gives a smart nod to the Piney Woods area, even if I totally made that up. Between his birth and his father’s death, Smith’s family had moved to Birmingham, Alabama, which is where his career in music began. A self-taught pianist, he broke in at age 15 playing house rent parties. Just a year later, he left the South for Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the city where his real education began.

Once in Pennsylvania, Pinetop Smith joined the Theater Owners Booking Association (TOBA) vaudeville circuit. He toured with the company handling everything from playing piano to singing to performing in skits. Paired with early-1920s blues legend, Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, as well as a singing husband/wife comedy team called Butterbean & Susie, he improved his piano playing; no less significantly, all that touring put the still-young Smith into juke joints and barrel houses all over the mid-Atlantic region and the American Southeast, places that exposed him to early blues and, of course, boogie-woogie.

While in Pittsburgh, Smith met another boogie-woogie pianist named Charles Edward “Cow Cow” Davenport, who convinced him to move with his wife, Sarah Horton, and their son to Chicago sometime during winter 1927 or spring 1928. Some mystery surrounds the origin and details of the relationship - for instance, Rag Piano relates a contested history in which Davenport introduced Pinetop Smith to the name “boogie-woogie,” a detail that runs headlong into Smith’s claim of coining the name - but, one thing is clear: Davenport had connections to the music industry in Chicago - and he definitely helped Smith in that regard. Apart from knowing Tampa Red - an important gatekeeper for musicians coming to Chicago during the Great Migration - Davenport was a musician/talent scout connected to Vocalion Records. That lead to introductions to J. Mayo Williams, a major player in the “race record” market in 1920s Chicago and the 1928 recording session that produced “Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie,” plus seven more recordings.

The truth of his claims aside, Davenport arranged a pretty smooth landing in Chicago for Pinetop Smith. He not only helped arrange those sessions, he connected Smith to Albert Ammons and Meade “Lux” Lewis, a couple of pianists who also played boogie-woogie; the three even shared a rooming house together for a time, presumably with Smith’s wife and, now, two children. Smith had another recording session lined up for March 16, 1929, but tragedy struck the budding community literally the day before when a bullet caught him at a dance hall performance. No one knows whether the bullet was intended for Pinetop Smith - it came out of a fight that ended with gunshots - but the headline in Downbeat magazine says it all: “I Saw Pinetop Spit Blood and Fall.” He died at just 25, leaving behind a wife and two kids.

The world kept turning and boogie-woogie continued after Pinetop Smith’s death - e.g., Meade “Lux” Lewis released his first hit, “Honky Tonk Train Blues,” in 1929 - but the Great Depression descended on the nation by the end of that year; when disposable income dried up, so did the record industry. Boogie-Woogie would go into a kind of remission for most of the 1930s. I’ll loop back to the story of its revival and cover the histories of some of the men who revived it - including Ammons and Lewis - in a (much) later post.

About the Sampler

I was happy to find all the songs from Pinetop Smith’s 1928 recording session on Spotify and included all of them on the sampler: in the order they have them, “I Got More Sense Than That,” “Pinetop Blues,” “Now I Ain’t Got Nothing at All,” “Big Boy They Can’t Do That,” “I’m Sober Now,” “Jump Steady Blues,” and, finally, a fantastic spin on a tune made famous by Bessie Smith, “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out.” [Ed. - If there's no link, I couldn't find it.] Beyond the playing - and boogie-woogie’s spirit of fun comes through - Smith gets a lot of personality into his music, enough to make you wistful about what might have been - especially after you hear Ammons’, Lewis’, et al’s later material.

I pushed the sampler to 20 songs by including a couple songs up above - e.g., Meade “Lux” Lewis’ first hit, as well as Albert Ammons’ first, the delightfully busy “Swanee River Boogie” - while also including three to acknowledge George Thomas: “The Rocks” (named for another variation), “Fast Stuff Blues,” and “Don’t Kill Him in Here.” Cow Cow Davenport also gets a nod - five, in fact - with “Chimes Blues,” (personal favorite) “The Mess Is Here,” “State Street Jive” (a duet), “Jim Crow Blues,” and, his most famous number (the one that prompted Pinetop Smith to introduce himself) “Cow Cow Blues.”

I’ve got one last song on there, something I couldn’t help but include as foreshadowing: Big Joe Turner’s “Roll ‘Em Pete.” I’m looking forward to telling that story.

Till the next one…

No comments:

Post a Comment