|

| How I'll remember him... |

Dick Clark: “You’ve had right good luck so far. Does the future scare you at all? You know once you get one hit you have to get the second. Now you’ve had two in a row. Do you worry about the third one yet?”

Terry Stafford: “Sure ... I think it’s always something that always scares you.”

Terry Stafford: “Sure ... I think it’s always something that always scares you.”

Terry Stafford, Oklahoma-born, Texas-raised, and hungry AF, will forever own the honor of, as one extensive biography phrased it, “breaking The Beatles stranglehold on the Top 5” in 1964. The song was “Suspicion,” a song that sounds like Elvis because Elvis had already recorded it in 1962, on the album Pot Luck with Elvis. If you listen to Elvis’ version against Stafford’s, you’ll hear why Stafford’s went further (or you’ll just like Elvis’ version better; free country) – and, along with Dick Clark, everyone wanted to know how Stafford (et. al.) produced those melodic accents. (They used an organ with paper bags over the organ’s speaker.) “Suspicion” topped out in the spring of ’64 at No. 3, between “Twist and Shout” and “She Loves You,” and Stafford was a young man on his way. (And, since I have it, here's Stafford's appearance on American Bandstand.)

He appeared on American Bandstand one more time – this time supporting “I’ll Touch a Star” – and that’s when the surprisingly prescient conversation quoted above took place. Stafford stayed in music until (at least) the 1980s (I tapped out on the extended bio around page 12), doing a lot of song-writing, but also enjoying a genuinely remarkable second act. It never went smoothly, but Stafford never gave up, and this quote from sometime in the early 1980s reveals a man whose spirit would not break:

“I never booked myself on any ‘oldies and goodies’ shows, because I feel my career has been progressing.”

In the first part of his career, Stafford relied on other writers – notably, Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, who wrote some of Elvis’ famous hits (including personal favorites like “A Mess of Blues,” “Little Sister” (cool video, btw), and “Viva Las Vegas” – and, on the back of the success of “Suspicion,” they fleshed out and released an entire album with the same title. In spite of having ample connections, Stafford’s days of recording as a knock-off Elvis lasted barely two years. Going the other way, those same connections opened doors for Stafford to start recording songs for movie soundtracks, and even appearing in some of them. His credits include, Le Spie Vengono dal Semifreddo (translation: "Dr. Goldfoot and the Girl Bombs"), and a 1966 sequel, Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine. He wouldn’t actually act until 1969’s Wild Wheels, where he played “’Huey,’ a dune buggy-riding surfer whose club tangles with a motorcycle pack,” and played “Wine, Women, and Song” over the fire at a clam-bake (good (dated) track, fwiw).

His second career started shortly after that, along with the rest of a life of writing signature songs for other artists. While on tour, Buck Owens heard Stafford’s song, “Big in Dallas,” on the radio in 1969 and thought he could make it into something bigger. He contacted Stafford and got his blessing to rearrange the song and change the setting, and that’s how “Big in Vegas” (here’s Stafford’s version) became such a big part of Owens’ repertoire that it was the last song he ever played according to that extended bio. Owens was, frankly, kind of a dick toward the man who did him a solid. As Owens put it:

“It was his idea and something that I enlarged upon. It worked out well for him because I’m sure it paid the rent one month.”

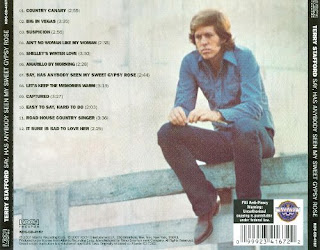

Perhaps (or probably) inspired by the success of “Big in Vegas,” Stafford started writing more in a country vein. He eventually landed on Atlantic Records fairly-recently launched country music division, where one of his key contacts, John Fisher, had started working. They assembled an “A-team” of session musicians and recorded Say, Has Anybody Seen My Sweet Gypsy Rose in 1973. The album was well-received critically, but the marketing side botched the roll out by failing to list “Amarillo by Morning” among the singles to promote. The song would very decidedly take on a life of its own, seizing air-play on its merits, and it was later re-recorded in 1982 by George Strait for his second album and, for the second time in Stafford’s career, he wrote a song that would bring fame to another man, but only the thinnest sliver of credit for him. Here’s the coda for that one:

“At the Country Music Association awards on November 6, 2013, with Strait sitting in the front row, hosts Brad Paisley and Carrie Underwood sang an ‘Amarillo by Morning’ parody, ‘Obamacare by Morning,’ much to the amusement of the audience with Paisley acknowledging Strait’s presence. ‘By the way, thank you, George Strait, I always loved [‘Amarillo by Morning”].’”

I want to close with the most fitting note possible for Terry Stafford. He recorded a second country album (I think) in 1973, which he titled We’ve Grown Close. Almost immediately after the first single came out – “Stop If You Love Me” – Atlantic Records folded its country music division and, without anyone to direct promotion, the album languished briefly, then faded away.

As I’ve discovered with a lot of alleged one-hit wonders, Terry Stafford put several hits into the world – hell, CMT named Strait’s version of “Amarillo by Morning” #12 in its top 100 country songs of all-time. I’ve been listening to both Strait’s and Stafford’s version of that tune since at least Tuesday, and it’s Stafford’s that’s growing on me (which is how it wound up on my May 2019, Week 3 MAME Playlist). That’s a song about keeping after one’s dreams, obstacles be damned. The same theme holds together, “Big in Dallas” and “California Dancer” (can't find this one), a song written by a woman who moves to California to turn professional dancer, only to have her dreams thwarted.

Stafford only tapped out when he died of liver failure in 1996. Here’s to hoping he died as proud as he deserved to be.

No comments:

Post a Comment